From the Baloch nightmare to the British "Guantanamo"

As told to Karlos Zurutuza and Wendy Johnson.

A shorter version of this article (Faiz Baloch: De la pesadilla baluche al Guantánamo "británico") appears at gara.net.

Photo by Karlos Zurutuza

September 1, 2010

"Did you know where Balochistan is the first day you came to this court?” I asked the jury. “Now you know where it is, and what’s happening to our people there.”

I was born in Western Balochistan. My family lives on both sides of what some people call “the border between Iran and Pakistan.” The name of my village is Kohak, and it is quite close to Panjgur town of Eastern Baluchistan (Pakistan-occupied Balochistan). Kohak was originally located in Pakistan, but our villagers tell us that one day they awoke to find themselves Iranian—the town had been given to the Shah of Iran. Nobody knows when the transfer officially took place.

|

"Did you know where Balochistan is the first day you came to this court?” I asked the jury. “Now you know where it is, and what’s happening to our people there.”

|

|

We don’t record our birth dates, but my guess is that I was born in 1982. Our way to remember is to relate our birth with something relevant that happened at the time; it can be big floods, a war, drought, etc. In my school documents it was recorded as 1982. Because we had few opportunities in Kohak—no school and no public transportation, only a mosque—my mother decided to send me to Quetta, Balochistan. The living conditions of the family on this side of the border were relatively better. I was around ten when I moved to Quetta for primary education. I went to high school and studied pre-medical at Baluchistan Degree College in Quetta, as well.

My college was filled with Marri boys—Baloch belonging to the Marri tribe—who had left Pakistan in the 70s to seek refuge in Afghanistan when Bhutto began a military incursion in the Marri tribal area. Now they had returned from Afghanistan in the 1990s to live in an area called New Kahan, very close to Quetta city. Here they had no facilities at all—no houses, schools, etc. I had myself experienced what these Baloch were going through. In the East we are discriminated against because of our ethnicity, but in West Balochistan there is also the religious factor because we’re a religious minority—Sunni Muslims, not Shia like the majority of Iranians. When I learned of the misery the Marris had suffered at the hand of Pakistan—and even in Afghanistan they had been repressed—I realised how difficult it had been for them and we became close friends.

Most of the Marris had no schooling certificates from Afghanistan, but local Baloch managed to get permission for older boys to enrol in Middle schools in Quetta. The younger boys and the girls, however, had nowhere to study. One of my uncles in Quetta was a friend of a local NGO called BLLF (Bonded Labour Liberation Front). He introduced the NGO to the New Kahan area and they were able to provide some school materials, but couldn’t afford to pay for teachers. The teachers were all volunteers. I taught, as well, but not full-time because I was still a student myself.

I was in my second year of college when Musharraf took power in Pakistan. This was followed by an escalation of army oppression in Balochistan. In January 2000, Musharraf’s army ravaged New Kahan in a joint military operation using paramilitary forces, police and Rangers. In one day alone 125 people were arrested; others disappeared forever. Following the operation I went to the area to see what had happened to teachers and friends. I remember I went in the morning—a very cold and cloudy day. When I arrived, I found the area deserted. The tents were destroyed; the windows of the houses smashed—as if a war had happened. All the men had been taken away. Only women, elderly men and children remained. At the damaged school I asked for my teacher friends. They had been arrested, as had many of the students. Almost three weeks had passed, but nobody had heard news of the arrested Marri men. Finally, after meeting with the remaining elderly people in the area, I decided to help. Along with two aged Marri men, I went to the police station to ask for information. But the police had no answers. They said they didn’t know—nobody knew where these people were being held and under what conditions. We eventually hired lawyers and petitioned the court about the arrests. I signed my name to this petition, along with two other Marri Baloch friends.

We first applied to a session court regarding the whereabouts of the Marri men. The Deputy Superintendent of Police, Criminal Investigation Department (DSP CID), Mr. Shahr Yar, the SHO (Station House Officer) of Shalkot police station, along with two other police officers, appeared in court to say they knew nothing about the Marri men. The lawyers then decided to approach the High Court. The court summoned the same police officers and instructed them and the ATF to either release the men or present them in court. The officers asked for three days to respond. Eventually the officers admitted that the Marri men were in their custody and had been arrested in connection with the murder of Justice Nawaz Marri who was killed in January 2000. They demanded more time to make a decision about filing charges and the court agreed, giving them another week or so.

During this period I managed to locate and visit most of the Marri detainees who were being held in City Police Station and Bijili Road Police Station. Some detainees we were unable to find. A friend who had connections with some police officials helped us; we also bribed a duty officer. One officer admitted privately that some Marris were in his police station, but that he couldn’t allow us to meet them. He told us to return after 10 am the following morning as the officers would not be there. He would then allow us to see them.

The next morning I arrived at the station and was told to stand next to a small room where some Pathans were detained. If the station officer returned, I was supposed to speak Pashtu and explain I was visiting the Pathans. I was given only five minutes to visit. The Marris were stuffed in a very small smelly room and shivering from the cold. They had been brought there two nights earlier. They told me that following their arrest they were separated between two police stations in Quetta. Each night 10-15 men would be transferred to Kulli Camp (Quetta Cantonment) where they were tortured by military intelligence (MI) until dawn. The interrogation rooms were located in a basement, painted black—with sharp objects hanging on the walls. Two officers would interrogate two detainees at a time, first asking basic questions. They would then send the men to a second room—this one had small holes in a wall. They guessed the dark adjacent room held informants who would provide details to the interrogators. Before I left, the men asked me to provide them some blankets because they were very cold.

As I left the police station, the officer at the gate (the one whom we bribed) suggested I approach the SHO to ask if there were any Marris in his custody and if I could bring them blankets. I thought about this for two days, worried that I might face arrest myself, but then decided to go ahead. Initially, the SHO reacted with great anger, but finally admitted that, yes, he was holding them. When he took me to their cells, he said angrily, “Look at their faces—they will bloody die and I will be in trouble.” He allowed me to bring blankets on the condition I not tell anyone. He indicated an office next to his and identified it as secret service. The surname on the door read Hazara. He said, “They should not know you have come here for the Marris.” The SHO assured me that he would contact the Bijili Road Police station and ask them to allow me to bring blankets for the Marris (I already knew the SHO of Bijili Road, but I didn’t tell him). The following evening a Marri driver and I distributed blankets and sweaters to all the detainees. The driver had visited Marri houses and collected the stuff. In one police station, ten men were held separately and we were not allowed to see them. Instead an SHO delivered the blankets. He had told me, “Dear, we follow orders. We don’t plan operations and we don’t know what happens to people once we arrest them and hand them over to the ‘Big Brothers.” We later discovered the men had been beaten so badly, their faces were bruised and so we weren’t allowed to see them.

The police eventually charged all 125 men with the murder of Justice Nawaz Marri and sent them to the Hudda district jail in Quetta. There they were under the control of the non-police security agencies, but the routine of night-long interrogations and torture continued. Visitors were allowed, but they were subsequently followed. Two were arrested after visits to their jailed relatives. The New Kahan area remained under siege following the formal charges. Police would patrol the area at night; and many men would not return to their houses for fear of being arrested.

I visited (once only) Hudda Jail in Quetta, where those who had been formally charged were held. There I managed to meet one of my teacher friends with the help of a lawyer friend and a bribe, yes—a bribe was required in this jail, too. My friend was in bad shape. His beard had grown long and he could hardly walk. We talked for half an hour in the presence of an official (the lawyer had business with the jail superintendent). My friend talked a lot, but we could not speak openly. “You’re also interesting man,” he said. I didn’t understand at first, but he repeated that “they are interested in you, too.” I told him to shush, said that I already knew that, for earlier that day MI had come to New Kahan and asked an elderly shop owner about me. The shop owner denied knowing me, but told me people claiming to be my college friends had been looking for me.

I started to worry about the safety of my relatives in Quetta. I could return to Western Balochistan anytime, but they were at real risk here in Eastern Balochistan. I decided I had to leave before anything happened to my family. And so I returned to my village on the border, where the line splits us apart. There I felt disturbed for a number of reasons: my education was incomplete, the situation was worsening for the Marris, as well as for the Baloch throughout Balochistan. I had never been interested in politics during high school and college. I was once asked to join the BSO (Baloch Students Organization), but I declined. I did join protests against the atomic blasts in Chaghai, Baluchistan, as well as some other demonstrations, but I was not a member of any party. The BSO was very influential my college and a member once told me if I didn’t join, I would not pass my exams. I was shocked to hear that.

In the summer of 2002, a friend in my village was arrested. There were political and religious problems in and around my village in Iran, particularly with a Shia missionary group who seemed to enjoy the backing of the security forces, and I decided I had to leave Baluchistan. I walked for some time, travelled by cars for a couple days, then boats. Finally I flew to London from a Gulf country. The issues that compelled me to leave were varied, but we had been blamed for supporting anti-Iranian “Baloch groups” who were characterized by the Iranian mullahs as “enemies of God.” In Iran “enemies of God” are hanged.

***

I landed in the UK on the 9th of September, 2002, and applied for asylum upon arrival. After my screening interview, I was sent to Coventry, a small city two hour’s drive from London. An elderly man whom I met in a Coventry library told me that “back in the days people would be sent to Coventry as punishment.” It is not specified as a location for asylum seekers, but there were relatively more asylum seeks in Coventry than anywhere else at that time.

Approximately three months later the Home Office rejected my asylum. They acknowledged that the Baloch faced troubles, but they had determined that I’d be safe if I were to return to Iranian-occupied Balochistan. I had the right to appeal the decision and so went to court, but they, too, rejected my application for asylum. Days later I learned that my friend who had been arrested in my village had now disappeared. The following week they found his body. Like me, he had experienced problems with the Shia ‘missionaries.’ I informed my lawyer and we submitted a new claim to the Home Office based on this development. During the appeal process I was not allowed to work, but the NASS (National Asylum Support Service) offered me housing and some financial support. When the court refused my asylum appeal, I was asked to leave the house and the support stopped. I moved in with a Kurdish friend I´d met in Coventry. It was 2005.

Only one Baluch family lived in Coventry, Shahin Shah Baluch. One day he rang to invite me to a Baloch demonstration in London. There I met many Baloch whom I asked for help. I wasn’t allowed to work and I obviously needed to do something to survive. Eventually I was introduced to the Marri brothers, Mehran and Hyrbyair, in Central London. When they learned of my work with the Marris of New Kahan, they offered to help. I returned to Coventry for a short while and then moved to London with my Kurdish friend, Mr. Bahman. We both rented rooms until Hyrbyair invited me to move into his place. His family wasn’t living in London at the time and he had plenty of space. Later, when his family arrived, he moved to a second house. I remained in the first house till the date of my arrest in December 2007. I believe I was arrested because of my friendship with Marri brothers, especially Hyrbyair, but also because I had become a regular participant in the demonstrations in London. I now was fully involved in activities that helped to highlight the plight of the Baluch people.

The website I set up in 2004 with fellow Baloch students in Eastern Balochistan, www.balochwarna.org, also became an important factor in my story. Now that I was living abroad, my friends suggested that I register our new site under my name—to remove any risk to students in Balochistan. Our mission was to report what the Pakistani and Iranian media and authorities would deliberately try to hide—news of the atrocities committed against the Baloch people.

At the same time, the story about Rashid Rauf, the transatlantic bomber, appeared in the press. Rashid Rauf had been arrested in Pakistan and was alleged to be the mastermind of the plot. In March 2007, Margaret Becket, the UK Foreign Minister, travelled to Pakistan in the company of a journalist from The Guardian. Ms. Becket told President Musharraf that the UK wanted to extradite Rashid Rauf. Musharraf reportedly replied that he wanted to extradite some Baloch living in the UK—eight Baloch. Two were the Marri brothers, Hyrbyair and Mehran, but no one knows who the other six were.

After that official visit to Pakistan, both English and Pakistani security services started to monitor Hyrbyair and Mehran’s activities, as well as that of their friends—stopping the friends at airports to ask questions, visiting their homes, etc. One of Hyrbyair’s friends, a British citizen of Pakistani origin, was returning to the UK from Pakistan. Pakistani authorities had him arrested in Dubai and extradited back to Pakistan where he was held in a safe house and questioned by the Pakistani army about Hyrbyair and his close friends. When the young man’s family, based in London, sought help from the British authorities about the arrest and extradition, they received a phone call from Pakistani Military Intelligence threatening that “If you want your man back alive, do not go to the embassy again.”

A week after the murder of Hyrbyair’s brother, Balaach Marri, I helped organize a memorial at London University. The following night I was editing the footage from the meeting for my web site. I stayed up late—I think I went to bed around 3 am. Two hours later—at 5:08am—a big “bang” and the sound of shouting woke me up. Suddenly, two men were sitting on top of me shouting, “Show us your hands!” They handcuffed me while I was still in bed. I didn’t know they were police officers until they turned on the lights. They asked me if I had any remote controls at home. I didn’t understand and led them to the living room to point out the TV controls. This made them very angry and they clarified that they were looking for remote controls for explosive devices. I had no such devices and told them “No, there is nothing in the house that explodes.” I still had no idea why they were arresting me and asking about explosives.

We waited inside the house while other officers checked the place. They then placed me in a police car, I guess for an hour or so. One of the officers wanted to chat and asked me about Balochistan. “So Faiz, tell me about your country Balochistan (he pronounced it as Balokistan)—Is it like Ireland?” “No,” I replied, “it’s similar to Kurdistan, but I’d describe it better as Palestine. It is pronounced Baluchistan not Balokistan! Unlike Kurdistan, Balochistan was a free country until the British divided it and later Iran and Pakistan occupied it.” The conversation continued for a while. Finally I asked the officials, “Why are we sitting in the car? Can’t we stay in the house?” “We took you out in the darkness so that you won’t be embarrassed in front of your neighbours,” said the officer. “The neighbours have already heard the banging and shouting—and there are two dozen cars around my house. They’ve seen everything already,” I replied laughing. It was the 4th of December, 2007. I would spend the next eight months in prison.

That night the officers took me to the Paddington Green police station where they took my fingerprints, DNA and filled out preliminary forms. I was then taken to a small prison cell and locked up for almost the entire next day. The cell contained a restroom and was monitored by video (CCTV). In the afternoon, two detectives came to my cell, shook hands, and told me a lawyer would arrive shortly to represent me during an interrogation. Before they left the cell, one of the officials said “Please, Mr. Baloch, try to be flexible with us.” I didn´t really understand what he meant by “flexible,” but I said OK. After an hour or so, the officer on duty opened the door to tell me my lawyer had arrived. He led me to another room where my lawyer was waiting.

The lawyer introduced himself as Fadi Jan Daud, a Christian Arab from Egypt. Before we started he apologised and said that he knew nothing about Balochistan. I was annoyed. “If you don’t know anything about my country, how can you represent me?” He was a very polite respectful man. “Mister . . . Fayaz Balock, if you tell me a little bit about your country and people, I promise I will do my best to help you—I’m not working for the police,” he explained with a broad smiling face. “My name is Faiz and I’m a Baluch not Balock,” I told him. “Oh, Faiz is an Arabic name.” He laughed again.

Before the interview, the police handed us a disclosure document that outlined the questions they were going to ask during the interrogation. Most of them related to the BLA (Baloch Liberation Army), the BRM (Baloch Rights Movement) and Mehran Baloch. Questions like: How do know Mehran Baluch? What is your affiliation with the BLA, if any? What is your affiliation with the Marri brothers? Are you working for the BRM? etc.

In the interrogation room I was seated with my lawyer and two police officers. They told me, however, that other people in the same building would be observing the interrogation. During the interview they also asked me how I had ended up in the UK. I just answered as best I could. Regarding the BLA, I told them I knew it existed, and that they were Baloch fighting for the independence of Balochistan, but I wasn’t involved at all as the police suggested I was. I had learned about the BLA through websites and news sources. They then asked me about the various Baloch websites. They had a list of most of the sites. They asked me who ran them. They mentioned BaluchSarmachaar.wordpress.com—what did “sarmachaar” mean? I answered their questions to the best of my knowledge. Later during another interview, their questions focused on www.balochvoice.com, balochwarna.com and balochunity.org. They thought I was running these sites.

The following morning my solicitor told me that I had the right to not answer their questions. That’s what I did going forward. He also told me he had spent the entire night reading about BaIochistan—the author Selig Harrison and other Baloch websites. “Now I know why they have arrested you and I know everything about Balochistan—look what I brought for you.” He pointed at a bundle of pages printed off the net. “All related to Balochistan. Oh, and I also brought you some oranges and dates which you can have later on,” he said smiling. He also told me that a friend of mine had been detained. He didn’t know his name.

Within 24 hours, a preliminary hearing took place via video link from the police station. That is when I saw Hyrbyair. My interrogations continued every day for a week, sometimes twice a day. Finally both Hyrbyair and I were charged with “inciting violence” and for “involvement in the Balochistan Liberation Army.” We were transferred to Belmarsh Prison*, Britain’s High Security prison where we were classified as “Category A prisoners.” Most people accused of terrorism and other serious crimes were category A. The majority of “Cat A” prisoners were Muslims.

According to the Govs (the term for prison officers) there were over 1,200 prisoners in Belmarsh. Cat A prisoners were held in private cells, while other prisoners were three to a cell. As Cat A prisoners we couldn’t receive visits without an invitation approved by the Home Office. Every time a Cat A prisoner leaves his cell, he is strip-searched on his return. We were confined to our cells for 21 hours a day. We would be taken out into the yard for exercise one hour in the morning from 8-9 am and for two hour breaks between 6-8 pm in the evening. The evening break was cancelled if there weren’t enough staff. There was a gym in the prison, but only accessible if one worked, and even then one could only use the gym for 40 minutes if it was not busy—too many Cat A inmates were not allowed in the gym at one time. After Hyrbyair was released, I was asked to work—mainly packing tea bags and biscuits for other prisoners. Those were the conditions for Category A prisoners, as I remember.

As a Baloch, one of the most degrading things for me was to get stripped; it was very humiliating. Each week they searched our cells. When the officers came by to announce search time, I would respond “humiliating time”—that was the hardest part for me. That and the dogs—they used to bring their dogs into the cell during the search and allow them to walk all over our beds, dining table, sniff our clothes, everything. We did have a small 14-inch TV, a kettle, a chair and table in our mini-cells. Most of the guards were very rude. They would swear a lot. Hyrbyair and I stopped talking to them. We would only speak if it was necessary to ask or answer a question. To them everyone was the same, whether he was a drug dealer, murderer or prisoner of conscience. One very young officer—he was a good man. He told us we were different from everyone else. When we told him we were Baloch and that we didn’t recognize either Iran or Pakistan as our country, he tried to explain this to the other guards—he was happy with us. Most of the food was not bad—mostly baked beans and half-cooked rice, but I’m generally used to food like this, so I had no complaints.

It was in Belmarsh prison that the brothers “Muslim inmates” suggested to me that I change lawyers because nobody knew them—their reputations were not well-established. Hadi Jan Dawood’s job had ended at the police station and he had introduced me to another lawyer—I don’t remember his name. The new lawyer was a good and polite man, but he knew nothing about Balochistan and he had not handled such cases. I was starting to worry. He used to tell me, “Mr. Baluch, please do not try to politicise your case; your case is simple.” “No,” I said, “it is not simple and it is already a politically motivated case.” In the meantime one of the brothers who was being represented by the Birnberg Peirce Law firm had provided me Gareth Pierce’s number and had strongly advised me to change my lawyer. I discussed the issue with Hyrbyair and we decided to apply for the change of lawyer. I rang Gareth and we arranged a video conference. She agreed to take on my case, but it took over a month to get approval. As I was not able to speak often with Gareth, my good friend in Wales frequently reminded her to take on my case. Eventually there was a court hearing via video conference because my previous lawyer was challenging the change of lawyer request. He said he had already spent money on my case and thought it unfair to make this change. I was told, however, that it was my right to ask for a new lawyer if I was unhappy with the assigned lawyer. The judge finally granted my request.

During one my next court hearings I finally met Gareth Pierce and Sajida Malik, both very kind and easygoing ladies. Gareth always looked serious, but Sajida was always smiling—she was very encouraging. Gareth introduced Sajida to me and said that “She will be visiting you, hopefully, outside the prison as we are trying to get you out on bail.” I was very relieved with this change in my lawyers—now I was in good hands.

In Belmarsh prison, we had made a lot of new friends, mostly brothers. We got to know them in the yard and during Friday prayer. Most of the inmates were really helpful and encouraging. “It is a testing time that Allah has brought on us and we will pass this test Inshaallah.”—This was the sentence repeated most often by the brothers. Though everyone was missing the food outside, we didn’t complain about the food. At night time we used hear the shouts of Window Warriors. Some inmates would shout things like “Hey bruv, how did your hearing go today?” or watch Big Brother or EastEnders (popular tv reality show and drama) and shout, “There’s a nice bird on bruv!” Then they would all start laughing uncontrollably. Whenever there was a football match, the window warriors would not let anyone sleep that night. The banging on the cell doors and shouting would continue till morning. Sometimes the shouting would escalate and turn into swearing, which would lead to verbal fighting over the football match. I remember the night Benazir Bhutto was killed. I had seen the news reports on TV, but later the window warriors spread the word. One of the men in the adjacent block shouted, “Hey Akhi, (Arabic word for brother) they killed BB!” “Yeah, Akhi mann, I saw it—served her well—she was against the Deen innit (she was against the religion, isn’t it so?)!” the other replied. Listening to window warriors was both fun and sad. Sometimes it made me laugh so much, but sometimes it was just swearing, even crying and screaming.

After five months, Hyrbyair was released on bail. Hyrbyair paid almost £300,000 for his bail security. Some of that money has not yet been returned to him. I was also scheduled to be released within the next couple of days, but to my surprise I instead received a notice stating that I was now being detained under immigration law. Because they had refused my asylum case, I now had to apply for a different type of bail through the Home Office. That decision dragged on for almost another three months. When Hyrbyair’s bail was approved, he insisted that he wait until my bail was also approved. “People will say that he left his friend and came out alone,” he said. I told him that it was nothing like that and that he should go. Let people say whatever they have to say.

When Hyrbyair left, they shifted me to another block, “the life-ies block.” Most of the people there were serving long sentences and it was relatively more relaxed than the previous one. This block was next to “a prison within the prison,” a place where the alleged Al-Qaeda leaders were kept. Abu Hamzah, the Hook Man, or the Claw Mullah, was also detained in this prison within a prison. Never did I see any inmate leaving or entering that place from that gate that faced me. All I could see were guards and their dogs.

After spending eight months in Belmarsh prison, my bail was finally approved and I was released. My Kurdish friend Bahman and his wife came to pick me up. The court didn’t request money for bail, rather they required two people to provide my surety. A good friend of ours, Mr. Raheem Baluch, graciously put up his house as security and Peter Tatchell paid £700. Thanks to both of these men, I was released. A third person was required to move in with me. My Kurdish friend Mr. Bahman, along with his family, moved in to fill that requirement. This was not a requirement of the court, but one my lawyers had suggested, so that I wouldn’t be alone in the house.

Though I was able to leave the house and visit with friends, it was still like a prison as there were very strict conditions attached to our bail. We had to wear a security tag 24 hours so that police would know my exact location all times. We couldn’t leave home between 8pm and 8am. We were advised against giving press conferences or attending any meetings related to Balochistan, Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan, nor could we phone anyone in those countries. We had to report to our nearest police station every day, exactly at the time fixed by the Court. Additionally, I had to answer a “voice recognition machine” once every hour during the night. After a week, the machine had really ruined my sleep and I requested the court to limit the number of calls. During the day I was trying to prepare my case in the lawyer’s office and I needed sleep. The judge decided they’d call me only once, before midnight.

There were five charges against each of us: (1) Possession of an article for a purpose connected with the commission, preparation and instigation of an act of terrorism – contrary to section 57 of terrorism act 2000. (2) Collecting information of a kind likely to be useful to a person for committing or preparing acts of terrorism – contrary to section 58 of terrorism act 2000. (3) Collecting information of a kind likely to be useful to a person for committing or preparing acts of terrorism – contrary to section 58 of terrorism act 2000. (4) Preparation of terrorist acts contrary to section 5 of terrorism act 2006. (5) Incitement to commit an act or acts of terrorism – contrary to section 59 of terrorism act 2000. Additionally, Hyrbyair Marri had been charged with possessing a CS Gas canister which comes under the fire arm act. Counts 2 and 3 seem identical, but they are regarding two different items.

The trial was to be heard by a jury of 12 men and women from a working middle-class neighbourhood. We were facing a 12-year sentence, but the length would ultimately be determined by the judge. And this judge we’d been told had a record of awarding long sentences. Also, the jurors were selected from a conservative neighbourhood that had a reputation for not being sympathetic to refugees. Lady Kennedy and Gareth had applied for a withdrawal of case because they felt there was no case, but this was denied. Sajida worried about me because she thought I was emotional and would get angry—she always advised me to avoid getting angry and defensive; she said you did nothing wrong. Just agree that yes, we did these things, but so what? What is wrong with what we did?

When the trial began, only then did we discover we had been followed since the death of Hyrbyair’s brother Balaach. The authorities (the counter terrorism branch of New Scotland Yard, I think) had installed cameras in front of my house to monitor my activity and had followed me almost every day. I remember some of their observations: exiting Sainsbury carrying ten bottles of water, buying medicine from Boots (a popular UK health and beauty retailer), shopping for a memory stick in Argos, printing out pictures of Balaach and shopping for a frame for the picture—stuff like that. I admitted all such observations were correct, but I didn’t understand how they made me guilty of a crime. Was it a crime to enter these shops? I didn’t think so; at least that is what I thought. The authorities also used my MSN conversations and text messages as evidence of my guilt, but again, all these electronic exchanges were typical of what an average person says; there was nothing sinister in my conversations and texts.

The prosecution also alleged that we’d been searching “dangerous words” on the internet—including names of people who could be potential targets. They also alleged that I had been trained and financed by Hyrbyair to set up my website and to promote his agenda through it. In fact, the mission of my site was to highlight the plight of the Baluch people and expose the atrocities committed by Pakistan and Iran—and that was every Baloch’s agenda, not just Hyrbyair’s.

To prepare for the trial, the prosecution travelled to Islamabad and several other countries to look for evidence against us. They even visited the US to investigate the company that hosted balochwarna.org on its servers. They secured a warrant against the company owner in case she refused to collaborate with the investigation. They only found what they already knew—what I had told them—that the website was registered under my name. That is all.

Next the prosecution turned to what they called “inflammatory statements” by Hyrbyair posted on the website. Our team pointed out to the jury that there were over 30,000 items on the website, including graphic evidence of atrocities committed by the Pakistani army—corpses of kids torn apart by aerial bombardment, artillery and rocket fire—“What about those?”

What I remember most about the trial is all the twists and turns of the prosecution and how the prosecutor tried to convince the jury that somehow we were linked to Al-Qaeda or other Islamic extremists. He showed some still images from Michael Moore’s movie (Farentheit 9/11) and told the jury that the Baluch have links with Al-Qaeda. I remember how their own expert on Baluchistan Mr Ion Talbot agreed that Pakistan has been very brutal to the Baluch people. During cross-examination, there was no single question that he disputed. He basically was of more benefit to us than the prosecution. The prosecution also tried to present me as a computer geek, which I am not.

Before the jury retired to consider the evidence, we had a chance to explain our side of the story. I spoke for two days and I think Hyrbyair spoke for three days. I told them that I didn’t think running a website should be a crime, especially when the Pakistani media reports nothing at all from Balochistan and even prevents foreign journalists from visiting the area.

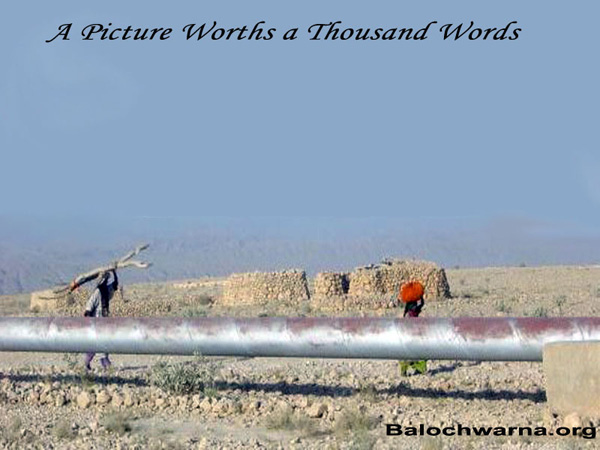

“Did you know where Balochistan is the first day you came to this court?” I asked the jury. “Now you know where it is, and what’s happening to our people there.” One of the pieces of evidence the prosecution tried to use against me was a booklet published by the BLA that was found in my house. A picture of a Sui Gas pipeline was printed on the back cover. An old lady carrying a big tree branch on her head was passing in front of the pipeline. “You can see the picture of the gas plant on one side and the mud houses on the other. Here people still cook with wood and dung. Gas was discovered in Baluchistan in 1952 and today we’re in 2008, our people still do not benefit from the gas. This is the story of Balochistan which Mr. Hill, the prosecution QC, doesn’t want to tell you.” I also told them that an independent Baluchistan was our goal and that our people are only defending themselves. “They are under attack and they have a right to self-defence.”

photo on back of BLA publication |

One of the pieces of evidence the prosecution tried to use against me was a booklet published by the BLA that was found in my house. A picture of a Sui Gas pipeline was printed on the back cover. An old lady carrying a big tree branch on her head was passing in front of the pipeline. “You can see the picture of the gas plant on one side and the mud houses on the other. Here people still cook with wood and dung. Gas was discovered in Baluchistan in 1952 and today we’re in 2008, our people still do not benefit from the gas. This is the story of Balochistan which Mr. Hill, the prosecution QC, doesn’t want to tell you.”

|

|

I also related my personal experiences and described the difficulties I had faced at the hands of the occupiers of my country. In the end, the jury saw through the spin of the prosecution and decided in our favour, they chose the side of the truth, rather than side with the oppressors.

Hyrbyair also very clearly expressed his point of view. He explained in great detail the situation of Baluchistan. Regarding the al-Qaeda allegation, he told the jury that we are against these people. “They were beheading us long before they started killing your people. We have been facing them alone without anyone’s help.”

It took four weeks for the jury to deliberate and render their verdict of not guilty. I was acquitted of all charges and Hyrbyair was acquitted of three charges. The jury was unable to make a decision on two charges. The pending charges against Hyrbyair were later dropped due to lack of evidence. The prosecution also decided that it was no longer in the public interest to continue the case. I was not in court the day the verdict was delivered—I regret that now (I was sick in the hospital), for Hyrbyair told me that one of the jurors had walked straight up to him after the trial to congratulate him on his acquittal and said, ‘Long Live Balochistan.’

My team worked really hard to prepare for my trial. I want to express all my thanks to Hussain Zaheer, Sajida Malik, Gareth Pierce, and Lady Helena Kennedy. Gareth had hired Hussain Zaheer, a junior barrister, and Lady Kennedy, one of the UK’s top barristers, to represent me in the Court. Sajida worked tirelessly. She visited Munir Mengal in France, Khan of Kalat in Wales and rang several people in Pakistan to ask for their help. She spoke to Imran Khan, Itezaz Ehsan, Ali Ahmad Kurd and Sanaullah Baluch. In the end, only Munir Mengal and Imran Khan gave evidence. The rest of the witnesses were not needed and some were reluctant to participate. The support of the Baluch Diaspora, especially Baluch and Sindhi friends in London, as well as Peter Tatchell, has been a great help to us. I also give a big thanks to all my Baluch friends who organised protests in the chilling cold weather of London and thank those who have offered moral support, either by sending me encouraging letters or with phone calls—whenever I could speak to them. Estella from CAMPACC Campaign against Criminalising Communities has also been of great help throughout our imprisonment, trial and subsequent acquittal.

To conclude, I will return to my asylum story. While the trial was underway, my team submitted a fresh claim to the Home Office for their consideration based on new evidence that had emerged during the trial, as well as the fact of my arrest and my naming and shaming in the international and national media. We pointed out that the UK government had made me vulnerable and that it is impossible for me to return to Balochistan as they have exposed me to the authorities of both Pakistan and Iran. To my surprise, they rejected even this new application for asylum and instructed me to return to Baluchistan. We decided to apply to the High Court for a judicial review of my case, but the UK Border Agency requested that we withdraw our appeal and informed us they would reconsider my case. Previously the UK Border Agency had determined that my situation had not changed in the UK since my arrival in 2002 and that I would face no problems if I were to return to Baluchistan. My argument is that my situation had changed considerably since I first applied for asylum in 2002: I didn´t have a website then, my attendance at Baloch demonstrations was not publicized and most importantly, I had not been accused of “terrorism” by the British courts. I’m obviously more exposed now than I was eight years ago. The collusion between Iran and Pakistan is well-documented. Pakistan routinely arrests Baluch and hands them over to Iran for execution by hanging. Iran similarly helps Pakistan. It seems evident to me that my life would be at risk if I were sent back to Baluchistan.

And what happened to the Marris whose case helped put me on the radar of the Pakistani authorities in the first place? Two of the men, Murad Khan and Dad Mohammad Marri, later died from the torture they suffered—after their release. Most of the men were eventually released on bail (bail money was never returned to them). A few were held by MI and never released. I never learned what happened to them.

*Between 2001 and 2002 Belmarsh Prison was used to detain a number of people indefinitely without charge or trial under the provisions of the Part 4 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, leading it to be called the "British version of Guantanamo Bay". The law lords later ruled that such imprisonment was discriminatory and against the Human Rights Act (see Wikipedia for details)

Karlos Zurutuza is a freelance correspondent from the Basque Country. He's been awarded with the

Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti Reporting Award 2009 for highlighting

the Baloch struggle in various newspapers and magazines. |